It’s a common statement in my family that listening to bluegrass music “brings out our hillbilly blood.” There’s something about its rawness and close ties to folk music that makes us nostalgic and gets our toes tapping and our blood pumping.

It’s a common statement in my family that listening to bluegrass music “brings out our hillbilly blood.” There’s something about its rawness and close ties to folk music that makes us nostalgic and gets our toes tapping and our blood pumping.

And of course wherever bluegrass is found, the banjo is sure to be at the center of it all. It’s a strange, twangy instrument, one that I’ve always enjoyed listening to. It’s an old instrument—pre-Civil War—yet artists are constantly adapting the way the banjo is played, passing down their tricks and talents to the next generation.

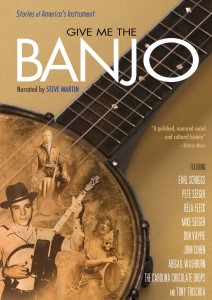

The documentary

Give Me the Banjo is narrated by Steve Martin, himself a great banjo player, and showcases the history of the instrument: its African and African-American roots, role in the creation of blues and bluegrass, its centrality to folk music, its importance in family life, and the recent resurgence of its mainstream popularity.

Banjo pioneers like Gus Cannon, Charlie Poole, Pete Seeger, and Earl Scruggs are profiled (and in Seeger and Scruggs’ case, interviewed), their lives and contributions interwoven into the history of the instrument. Each man had a singular effect on the banjo’s popularity or playing style — without them, the banjo would not be the instrument, or make the same sound, it does today.

A little history

I knew that the banjo was invented in the rural south—where else in America would it happen?—but I didn’t know it was invented by African-American slaves. Starting in the 1830s it became a feature of minstrel shows, as much a stereotypical (though less offensive) symbol of African-Americans as drawings of big lips and ears.

After the Civil War and through the 19th century, the banjo launched two separate types of music: blues and bluegrass. The former, played mostly by African-Americans, took deep root in places like Memphis and New Orleans, while bluegrass was synonymous with places Kentucky and Tennessee.

From the 1940s to the 1960s there was a “Folk Revival” in the US, a sudden interest in the folk music and dancing of earlier decades. People like Mike Seeger, brother to Pete and a talented banjo player himself, traveled around the American South, interviewing rural musicians and preserving their songs for posterity.

In more recent years artists like Béla Fleck and Tony Trischka have worked to bring the banjo into the mainstream. Almost everyone loves it, but young urbanites in particular are drawn to the sound, and are eager to learn and pass their passion on to others.

An oral tradition

I’ve always loved the sound of the banjo, and of bluegrass and folk music, but it wasn’t until I watched this documentary that I realized exactly why. In the words of Mike Seeger:

This music exists to entertain a few friends, and not for performance. And it can happen anytime, anywhere, and I think it’s wonderful for that reason.

Much like Sacred Harp, the banjo and the music it creates is a communal experience, one meant to be joined instead of watched. In many places it continues to be oral tradition passed down through the generations — Earl Scruggs, arguably the best banjo player in the world, couldn’t read music at all.

As Steve Martin says, banjo music has “always been music made by neighbors, for their neighbors.” It’s a way to come together and create something new while paying homage to those who have come before.

It’s yet another form of storytelling, one almost as old as America itself. And I don’t see it losing popularity anytime soon.

I watched Give Me the Banjo as part of Non-fiction November. Click the image to see posts from this and previous years!