In preparation for the Texas Sacred Harp Singing Convention later this month, I’ve been trying to dig a little deeper into the history of the music. I’ve been shape-note singing for a couple years now, and it seemed a bit shameful that I hadn’t read much about its roots.

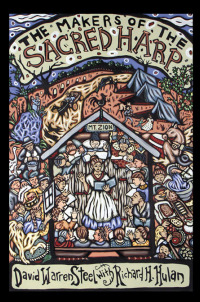

The Makers of the Sacred Harp

This book is divided into four sections: The Book, The Words, The Composers, and The Songs.

This book is divided into four sections: The Book, The Words, The Composers, and The Songs.

The first two sections were definitely the most interesting, as they cover more of the history of the Sacred Harp tradition and songbook. The other half of the book was interesting, but ended up being more a set of mini-biographies and publication dates.

What I wanted from Hulan’s sections was a look into the words of the songs themselves. I wanted more history, more story. In my opinion he spent too much time on music theory and not enough on trying to explain the power of the music.

At the end of the day The Makers of the Sacred Harp feels more like a series of essays and a reference book than a cohesive unit; which makes sense, considering its authors are a music/southern culture professor and a folk hymnody scholar.

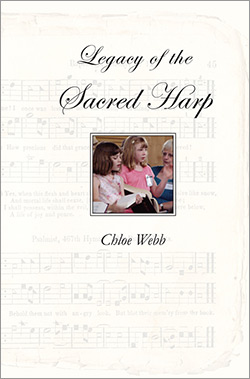

Legacy of the Sacred Harp

While Steel and Hulan’s book takes a high-level approach to the history of the music, Legacy of the Sacred Harp is a personal memoir by singer Chloe Webb, who in the late 1980s set about tracing her family line. She’s a descendent of the Dumas family, a name well-known in Sacred Harp.

While Steel and Hulan’s book takes a high-level approach to the history of the music, Legacy of the Sacred Harp is a personal memoir by singer Chloe Webb, who in the late 1980s set about tracing her family line. She’s a descendent of the Dumas family, a name well-known in Sacred Harp.

Webb’s book reads a bit like an analog Ancestry.com, replete with references to poring over old records in dusty reference libraries, ancient white clapboard Primitive Churches, and parallels between her research and life.

While I enjoyed the bigger historical lessons—slavery, Jamestown, the rural south—I’m afraid Webb’s book just couldn’t keep me hooked. At nearly 26 I’m only just now becoming the slightest bit interested in my own ancestry, nevermind someone else’s. Webb’s research goes as far back as the 16th century — she discusses what feels like dozens of ancestors, and I can’t keep them straight. It doesn’t help that the family tree diagrams listed in the book aren’t laid out that well, making them harder to use as references.

My favorite parts were actually the earlier chapters, in which Webb discusses her own re-discovery of shape notes, and the connection it gives her to her grandmother. Much like when I read A Sacred Feast, I loved reading about the author’s first experience at a big singing: emotional, visceral, immediate.

Webb is a great writer, capturing beautifully in just a couple sentences why Sacred Harp matters so much its singers:

We become one vast choir linked across the centuries. The music of the sacred harp gives wings to the soul, lifting it beyond earthly cares to soar for an ecstatic moment in the realm of the spirit.

Moving forward

I don’t think this is the kind of history one learns from books. Put to paper it’s just a bunch of dry, chronological facts; the composers and writers lived so long ago that it’s impossible to know much about them.

The only real way, I think, to learn about Sacred Harp is to sing it — the music flows through your blood and makes your bones hum. Or as writer Simon Jones put it:

The sound is like nothing I have ever heard before…It’s as deep as funeral music, but feels like a resurrection. When Michael invites newcomers into the hollow square to get the full surround-sound experience, my insides crack like a flagstone.

Perhaps I’m not even interested in the history, for that implies that the music is old, dead and gone, and fit only for dusty tomes in back rooms.

But Sacred Harp is alive! It lives on through its singers, people I’ve met like Mike Hinton (descended from the Denson family) and Leon Ballinger — the man makes a noise like a foghorn and always things we’re singing too slow, and I love sitting next to him in the hollow square.

I love this tradition, and it doesn’t really matter from whence it came. All that matters is that it’s still going, and that are people ushering it ever forward into the future.