No culture has mastered the fine art of complaining better than the Jews. Separate from Hebrew, Yiddish is a complex, nuanced language not for the faint of heart. Meant to lament bad luck while chasing it away at the same time, Yiddish tells the story of a culture all its own.

No culture has mastered the fine art of complaining better than the Jews. Separate from Hebrew, Yiddish is a complex, nuanced language not for the faint of heart. Meant to lament bad luck while chasing it away at the same time, Yiddish tells the story of a culture all its own.

There are phrases for cursing, food, sex, death, and everything in between; double entendre and metaphor are the rule.

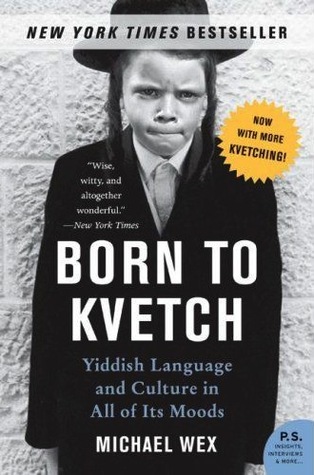

Born to Kvetch: Yiddish Language and Culture in All of Its Moods is an etymological and cultural look at the origin of Yiddish, as well as how Jewish experience constantly reshapes the language.

Tough, but fun

The first three chapters or so of Born to Kvetch were challenging. Author Michael Wex gives a high-level history of the origins of Yiddish, and goes into some detail about Talmudic law and specific disagreements about pronunciation…it’s important information, just a little too dry.

Once the ball got rolling, though, I really enjoyed reading about this whip-smart (and whiplash-causing) language.

More than meets the eye

[pullquote]I’d compare Yiddish to an iceberg: what you see is merely a portion of a phrase’s full meaning.[/pullquote]

I’d compare Yiddish to an iceberg: what you see is merely a portion of a phrase’s full meaning.

For example, check out the phrase lign in dr’erd un bakn beygl (lying in the ground, baking bagels). “Lying in the ground” can be interpreted as being dead, but the phrase itself means that the speaker’s plan isn’t going as well as he or she may have wished.

It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense until you think on the deeper point:

…it’s as if being dead isn’t bad enough, you’ve got to spend all of eternity in hellishly hot bakery conditions, baking bagels that, being dead, you have no need to eat; that, being dead, you’ve got no one to whom you can sell them; that, being dead, you don’t even know anybody except other dead people, who also don’t need to eat and who also don’t have any money and who are all busy baking their own lousy bagels that they can’t get rid of either.

Talk about an artful complaint!

Avoiding evil

Superstition is a big part of Yiddish, and often the language is used as a kind of code to show people you care without attracting potential new evil — be it from the persecutors of generations past, or the demons that lurk everywhere ready to bring the evil eye down upon an unsuspecting family member or friend.

Mostly this involves making a compliment seem like a complaint or curse: “Is she beautiful? My enemies should be as ugly [as she is beautiful]!”

There are dozens of this kind of example in Born to Kvetch; they’re my favorites because they remind me of growing up near Mexico, where the mal ojo (evil eye) can be warded away from things or people you love or find pretty by simply touching them.

The ideal coping mechanism

There’s a popular saying among comedians that men complain about their problems because they want solutions; women complain just because they want to.

Yiddish is kinda like that.

A kvetch might make things easier to bear, but it doesn’t actually try to change the things it’s kvetching about; it’s a way of dealing with circumstances and situations that we feel powerless to change.

Sometimes it feels good to just bitch about something. Now I just need to learn Yiddish so I can do it right.

What’s your favorite thing to kvetch about?