I’ve read lots of books in my lifetime (my guess is somewhere around eleventy-million), but I don’t know much about books themselves: who first created them, how their mode of creation and distribution has changed, and how people think about them.

I’ve read lots of books in my lifetime (my guess is somewhere around eleventy-million), but I don’t know much about books themselves: who first created them, how their mode of creation and distribution has changed, and how people think about them.

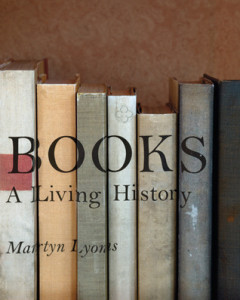

Fortunately there are men like Martyn Lyons who think to catalogue these things. His book, Books: A Living History, is just that: the history of the book from its earliest incarnations until the 21st century. From clay tablets to e-readers, from East to West, this book has it all.

Books have changed

Looking back, it’s amazing how far the idea of the book has come. Most avid readers are aware of things like the invention of papyrus, and of Gutenberg’s printing press; but there’s so much more to learn.

For example, Gutenberg was not the first to invent movable type; the Chinese were using it by the 11th century, and the Koreans by the 13th.

The nuts and bolts of the book—how paper was first created, how people invented better and more efficient machines for creating both text and imagery—are interesting, if not always clearly explained (I had to read the description of how the first printing presses worked several times and still didn’t quite understand).

It was also cool to see this development on a global scale. Different technologies developed at different times in different places, and succeeded or failed for different reasons. It was interesting to see how these timelines interacted.

Also fascinating was the sheer scope of books on which Lyons offers information. Of course religious texts were the main fare for many centuries, but printing technologies also affected how scientific research was shared, how cartographers displayed their maps, how biologists shared images of the flora and fauna they discovered.

Lyons touches on the evolution of typography, censorship, literacy, book binding, how books were shared in communities, the publisher and the ebook, book illustration and design, the rise of the children’s book, and so much more.

The facts were great, but there was an even deeper topic that I loved more.

Views on books have changed

Books have never been so common in the world as they are now. In the 21st century you can find books for sale in grocery store checkout lanes, in secondhand shops, at libraries, and even download them directly to your favorite handheld device.

This was not always the case. For example, Thomas Jefferson’s personal collection of 6,487 books was one of the largest in the country when he sold it to the Library of Congress in 1815. These days almost everyone I know is within a 20-minute drive of the nearest Barnes and Noble where easily twice that number of books is available for purchase.

Because books were few in number, and difficult to make, they were considered sacred objects. Scribes in places like Germany and Israel spent their entire lives creating just a handful of books, built and decorated by hand.

As books have become plentiful in most parts of the world (and in many cases downloadable), it’s easy to see that they are no longer held in such high esteem. Copies are left out in the sun to fade, dropped in pools, used to balance wobbly tables, and sometimes thrown away.

As a bibliophile, this loss of sacredness is saddening to me. I don’t want books—the words as well as the physical objects themselves—to become less valuable in our eyes. Fortunately tomes like Books: A Living History preserve that knowledge and give us new ways of looking to the future.